Somali is a Cushitic language spoken by over 24 million people across the Horn of Africa and the Somali diaspora. With roots likely dating back to the first millennium BCE, Somali boasts a rich oral tradition of poetry, storytelling, and proverbs.

For centuries, Somali was almost exclusively spoken. Oral literature served as the primary medium for sharing culture, history, and wisdom. Stories passed from generation to generation, often told around the fire at night. Poetry—especially gabay—was central, used to convey news, resolve disputes, express love, or satirize rivals.

As the Somali proverb says:

“Somalis may lie, but they don’t lie in proverbs.”

The spoken word held more authority than the written for much of Somali history. This blog explores how Somali transitioned from oral to written form and the key milestones that shaped its modern literary identity.

Early Attempts to Write Somali

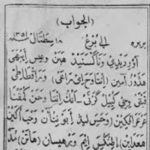

Arabic Script & Wadaad’s Writing

The earliest attempts to write Somali used the Arabic script, reflecting the strong influence of Islam. Religious scholars wrote poetry and religious texts in Arabic, often mixing in Somali words. However, the Arabic script couldn’t accurately represent all Somali sounds—especially its vowels and certain consonants.

To address this, Wadaad’s writing emerged, a modified version of Arabic script primarily used by Islamic clerics. It aimed to write Somali phonetically using Arabic characters, but it remained limited in use and reach.

Wadaad’s writing (from ‘Somali Letter in Far Wadaad YouTube – Aziz Faarah)

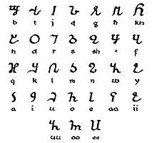

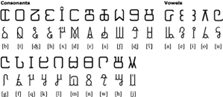

Indigenous Scripts: Osmanya, Borama, and Kaddare

In the 20th century, Somali scholars developed three indigenous scripts:

Osmanya: Created by Osman Yusuf Kenadid in the 1920s.

Borama: Developed by Sheikh Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur for the Gadabuursi community.

Kaddare: Introduced in the 1950s by Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare.

Each script offered unique solutions for representing Somali phonetically, but none achieved nationwide adoption.

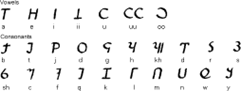

The Latin Script: A Turning Point

Following independence in 1960, Somalia faced a national debate: which script should officially represent the Somali language? The turning point came in October 1972, when President Siad Barre declared the Latin alphabet the official writing system.

Developed by Shire Jama Ahmed, this script was selected from among 18 competing orthographies. It was:

Phonetic and regular

Easy to learn and teach

Free of diacritics (except an apostrophe for the glottal stop)

Written left to right using Latin letters (excluding p, v, and z)

A Literacy Revolution

The adoption of the Latin script sparked one of Africa’s most successful literacy campaigns. Thousands of Somalis became literate in their native language. Somali was now the official language of government, education, and media. This reform laid the foundation for a growing body of Somali literature, newspapers, textbooks, and digital content.

Adapting to Change: Somali in the Modern World

Like all living languages, Somali continues to evolve—absorbing influences from religion, colonization, globalization, and technology.

Sources of Borrowed Vocabulary

Arabic (due to Islam): salat (prayer), kutub (books)

Italian & English (colonial/post-colonial): bastoolad (from pistola), telefishin

Modern English (global media/tech): internet, mobil, kombiyuutar

Urban Somalis are more exposed to global media and technology, resulting in a more hybrid language. In contrast, rural and nomadic communities preserve more traditional Somali vocabulary.

Risks to Native Somali

Language change isn’t inherently negative. But over-reliance on foreign words—especially when Somali equivalents exist—can gradually erode linguistic heritage.

Potential threats:

Native terms being forgotten or replaced

Lack of standardization in technical fields

Youth undervaluing native vocabulary

Protecting and Growing the Somali Language

Somali is not at existential risk—but active effort is needed to preserve its richness and independence.

What Can We Do?

Coin Somali terms for new technologies and concepts (e.g., kaamirad for “camera”)

Encourage native expressions in media and literature

Standardize terminology in science, tech, and law

Teach language awareness in schools and diaspora communities

Somali must remain dynamic and relevant—while preserving the essence of its oral and written heritage.

Conclusion

The journey of Somali from an oral tradition to a written language is remarkable. From ancient gabay poetry to modern digital media, Somali has proven resilient and adaptable.

The 1972 adoption of the Latin script empowered generations of Somali speakers to read, write, and preserve their culture. Today, the challenge is to protect the native core of the language in the face of rapid change—by nurturing it in classrooms, books, homes, and online.